home \’hom\

noun

: the place (such as a house or apartment) where a person lives

: a family living together in one building, house, etc.

: a place where something normally or naturally lives or is located

(from Merriam-Webster dictionary app for Ipad)

I had wanted to make this journey long ago, to see the house where the great man lived, and for most of his life, worked in. I had nursed this idea for about fifteen years, when I met his daughter Ijeoma. She was my colleague at the African Foundation for the Arts, Lagos. I wondered how it felt like, living with Uche Okeke.

Having seen him many times, albeit from afar- at the times when he was recovering from a stroke, I never really experienced the man. He was usually silent, with a knowing smile playing on his face. He had a fixed smile that seemed to mock one. And his wife and daughter were always with him, taking him out for select art-related functions.

I have always been interested in history and biographies. The life of artists fascinated me. I had long resigned to the fate that that was my path. I was making history. I had visited other artist friends/ mentors and always went away with an education. Uche Okeke’s Asele Institute was in Nimo, a few miles from Awka, the Anambra State capital.

Ijeoma travelled to South Africa to live and work, while I returned to studio practice. I soon met Salma, Ijeoma’s elder sister, and started asking for a visit to Nimo. That was about eight years ago. No one lived there, she said. Uche Okeke had relocated to Lagos to recoup from his illness in Lagos.

A few days to his funeral, I put a call to Salma asking to visit Nimo to pay my condolences and see the final resting place of the man who built the foundations of the Nsukka Art School. Salma and Ijeoma returned to Nimo on the day I came calling. I drove from my studio in Oguta through the curvy hills and valleys between, driving through Ihiala, Nnewi, and Nnobi, to Nimo. I stopped at Neni to take a picture by the statue of Power Mike made by my dear friend Chijioke Onuorah. The very realistic work showed the international champion wrestler as a man whose feet seemed firmly planted into the earth, guarding the entrance and roundabout to his hometown.

The turn in the left led to Nimo, Asele Institute was about ten minutes’ away. Salma’s phone was busy so I got the directions to the man’s house from an elderly lady I saw selling recharge cards by the roadside. ‘Go straight down the road, and just before you get to the hospital, take the dirt road on your right. You will see his house’, she said.

Asele Institute was familiar- it must be from some art catalogue or so. The real thing gave me mixed feelings. It seemed the man with great ideas had great dreams. Scattered around the huge compound were houses that had just been started, but lay unfinished and abandoned. The three-storey main house looked like something growing from the ground, as though it would never be complete. Packed under, by the entrance, was an old blue Citroen. The man had class. He had lived well. Something about the house reminded one of Demas Nwoko, longtime friend and fellow alumni of the Zaria School. There was something about the ‘finish’ of the walls.

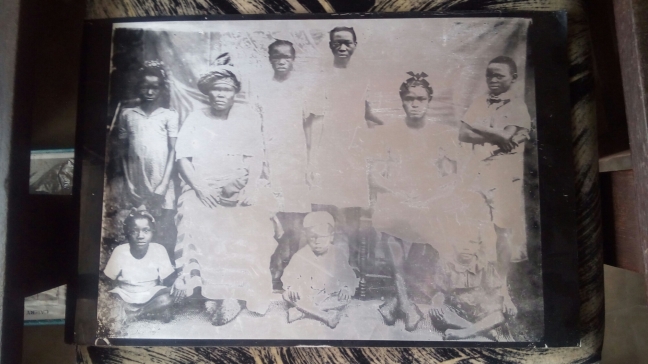

I first climbed up to pay my condolences and catch up with my former colleague and friend Ijeoma. We hadn’t seen in a decade. The sun had gone down when I toured the ground floor gallery. It was full of Uche Okeke’s works, and the works of a few other artists- Chike Amaefuna’s beadworks, and a large oil painting by Tayo Adenaike, the renowned Uli watercolorist, and some other artists whose names were not so familiar. I again felt the persistent guilt of not knowing enough of my country’s art history. Firsthand, I was reminded again of the darkness of Uche Okeke’s works. He seldom used whites, preferring to build tonalities in layers that brought out various intensities, and brilliance. The pieces glowed eerily, from within.

The gallery looked abandoned, as a place that was shut down for eight years would be. For so long, the house had stayed empty, a dark place full of dust-clad treasures. Did the man become less and less important due to his illness, when he stopped worked? Or did the place loose its significance with each passing year of abandonment?

On my Facebook wall, I had announced the funeral plans for Professor Uche Okeke. Shockingly, former alumni at Nsukka asked me who the man was! And the man was not yet buried, at the time! The topmost floor of Asele Institute housed a library of books, I was told. That place was sealed off. The books in a library at the first floor looked weather-beaten.

Uche Okeke had built a mini amphitheater by the gate to the expansive compound. The Society of Nigerian Artists would renovate the place for his lying-in-state, I was told. Uli designs will be painted round the small walls of the deep space. The man would have been happy. He had lived a great life. Do you realize that Uche Okeke’s work has had a strong influence on the works of many artists, I asked Ijeoma on my way out of the house. Yes, she said, ‘That was the way he wanted it’. He wanted to show the way. The man was a pioneer.

Uche Okeke opened the door, showing the possibilities and inspiration that can be tapped from accessing our local spaces. Relocating my studio to Oguta was partly affected by this sense of homecoming, of returning to one’s roots to appropriate and relocate interpretations of the new life. Uche Okeke lived in a town of small hills and valleys. For most of his active life, the man looked down an unobstructed landscape of small houses. His house was a towering edifice that barely contained the man. He will be buried in a few days, but I will not be there to join the expectedly rich crowd of artists, friends and art enthusiasts to bid the man goodbye.

The creative genius must be at peace now. His house showed that a restless force had passed by. A great wind had blown through in an untamed blast. Death for an artist is merely a transition of a presence. The materiality of mortality is but a small thing, really. We relive and recall his life and works every time we work, particularly among those of us who got close to the Nsukka Uli School. I saw the artworks scattered everywhere. Their value must have tripled with the artist’s demise. But this is stating the economic impact of the loss. The man lived, loved, and left behind loved ones who mourn him. He will be forever remembered for the post-colonial calls to artists to appropriate materials from their local spaces in building new interactions. In the end, nothing else really matters. The artwork is self-explanatory. The man died, we all know, after a long and fruitful creative life. May this be my way, with all the lessons learned. May his soul rest in perfect peace. To another life.